Interview with Cory Gustafson, Healthcare Administrator / Former Medicaid Director

“I don’t think we have a critical mass to sustain a healthcare system at the level of quality that Vermonters expect in terms of care.”

-Cory Gustafson

A Career in Motion: Hockey and Healthcare

Cory Gustafson did not know that he wanted to work in healthcare until he faced retirement a short ten years post-college. Another ten years later, he was leading Vermont’s public health insurance plan and managing its $1 billion operating budget.

The Canada native first moved to the United States when he was recruited to attend Harvard to play hockey. After graduating, he spent the subsequent decade playing the sport professionally, predominantly in Germany. Upon his sports retirement, he and his wife Katie faced a cascade of life changes as they simultaneously prepared to welcome their first child and moved back to her hometown of Montpelier, Vermont to be near family.

Amidst all the change, Cory also had to figure out how to follow his professional hockey career. After a law internship within Vermont’s statehouse in Montpelier, Cory was hired by a trade association that lobbied on behalf of Vermont hospitals. Thus began his second act career in healthcare policy and administration.

Cory grew his career across the Vermont healthcare ecosystem. He went from his lobbying position to work at nonprofit commercial health insurance plan Blue Cross Blue Shield of Vermont. Next, he was hired as Commissioner of the Department of Health Access for Vermont as part of Governor Phil Scott’s first administration. In this role, he led Vermont’s Medicaid program from 2017 to 2021. In his latest career change, he joined the University of Vermont, the state’s largest hospital system .

“My career has been about being part of teams,” he explains. “[It is] not just about who you work with but the problem you work on. In Vermont an overarching goal is to take the healthcare system from where it is today to a future state that is more affordable and accessible, with higher quality.”

Few Neighbors, Lots of Hiking Trails

There is a certain amount of whimsy inherent in a state whose notable exports include maple syrup, Ben and Jerry’s, and folk pop singer Noah Kahan. Visitors agree, with a whopping ten percent of Vermont’s economy attributed to tourism, with “flat landers” visiting the mountainous state to enjoy its mild summers, autumnal “leaf peeping” season, and wintertime ski season.

Vermont (population: 650,000) is a bit of a paradox. It is arguably a healthy state, ranked in the top five healthiest states by the UnitedHealth Foundation in 2023. It is also arguably a wealthy state, with per capita Vermonter net worth at approximately $275,000 and household net worth approximately $650,000 in 2023. Despite this, many residents still struggle to manage their health and financial needs without support. In 2022, approximately a third of Vermonters received health coverage through needs-based Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (which operates under the name Dr. Dynasaur in Vermont), ranking ninth among states with the highest percentage of residents enrolled in these programs by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

Physical activity and outdoorsmanship are integral to Vermont culture and support the state’s health rankings.

“The active nature of Vermont has a flywheel effect…People are up to try and do things together which is the tie that binds communities,” Cory describes. With a lengthy list of physical hobbies – playing in a recreational hockey league, skiing, golfing, and swimming – he embodies this Vermonter attitude perfectly.

Beside contributing to the health of the state, Cory sees that the active culture can seemingly melt social stratification, at least to an extent.

“Income gaps can be a delineation between groups of people and because of the active nature in Vermont there might be less of a barrier to connection,” he theorizes.

Another part of the value proposition of Vermont is the lack of people, beat only by Wyoming as the state with fewest residents. The low-density environment enables the preservation of scenic open space that drives tourism. It is peaceful and quiet, and locals and tourists alike want it to stay that way. It also contributes to the small town feel of the state.

“There are just not that many people in Vermont, so a benefit is that six degrees of separation feels like two degrees,” Cory adds.

However, there are certainly key economic downsides associated with the scarcity of Vermonters, and these carry over to its healthcare workforce as well.

“On the economic side it is tougher. There is not an abundance of opportunity so a lot of people take what they can get for work given that they appreciate the quality of life in Vermont.”

The Political Arena

Montpelier (population: 8,000) is the nation’s smallest capital and the only one without a McDonald’s or Starbucks. Walking distance to Cory’s home, the historic downtown surrounding the Capitol boasts a delightfully high number of bakeries, vintage and antique stores, and alternative wellness businesses on a per capita basis, often with counterintuitive operating hours. It’s not uncommon for neighbors to leave castoff home goods or excess homegrown produce at the end of their driveways as giveaways. The local composting facility employs a team of donkeys that pull a cart across town to pick up food scraps from downtown businesses. In February an alleged “Valentine Bandit” decorates storefronts and other windows around town with a matching cartoon heart printout, but you can usually find at least some of the lingering posters up year-round. Come summer, post-hibernation bear sightings across town set the virtual Front Porch Forum abuzz with ursine updates.

Vermont’s political landscape is similarly unique to its capital. Vermont was the first state to ban billboards. Composting is legally mandated (good job security for the donkeys). Vermont consistently sends liberal Senator Bernie Sanders to Congress, and Republican Governor Phil Scott is also on his fourth term and polls as one of the governors most popular with his constituents. The self-described fiscally conservative and pro-choice Republican governor endorsed President Biden in the 2020 election, perhaps a paradoxical web impossible to untangle in another state but indicative of how Vermont politics are their own arena. Speaking of arenas, the governor is also a hobbyist racecar driver.

“There is a compromise identity in the halls of the statehouse and policy realms. You really get to know people. You can’t see them as evil; you see them as human with different views… Neighbor to neighbor, people are pretty accepting of others,” Cory describes.

Even with this foundation, Cory notes that Vermont is not immune to growing division in national politics. Nor are Vermonters homogenous in their views. Compromise across party lines has become more difficult locally as national division sparks a greater sense of political tribalism.

Public Health Pressures

Vermont is not without its public health challenges. Like much of the country, Vermont continues to struggle deeply with the opioid epidemic. In 2023, there were 234 opioid-related deaths statewide, more than tripled from a decade prior. Per the CDC, nationally Vermont ranks ninth for worst age-adjusted drug overdose mortality.

Homelessness is also a major concern. Approximately 3,300 people experienced homelessness in Vermont in 2023, about tripled from 2020. According to the Vermont Housing Finance Agency, the median price of a Vermont home increased in 2022 by 15% from the prior year, the largest annual increase since data collection began in 1988.

Cory notes that while the exact relationship can be nebulous, the interplay between homelessness and the opioid epidemic exacerbates both challenges.

“Opioid use can trigger someone not being able to keep housing, or [for] someone not able to keep housing, they might turn to [opioids] available on the street to manage their days and emotions,” he explains.

Generally, in Vermont the political debate focuses on what specific steps the state should take to help those affected.

“Part of the social fabric of Vermont is the desire to care for your neighbors. Vermont tries to take care of its people that need a hand,” Cory attests.

One such intervention is a program where the Department of Mental Health Access deploys nurses throughout the state to provide health checks on Medicaid beneficiaries with complex social and health needs. Cory describes that having medical personnel check on these beneficiaries is an important service for the rural state where these individuals could easily slip through safety nets.

“The department recognizes that the social determinants of health can really impact a person’s ability to recover and habilitate. People can get better in the right situation,” he shares. “There are so many good programs in Vermont related to the social determinants of health…There is this network of entities spread across the state.”

Vermont’s low-density environment creates natural barriers for healthcare access. Reflective of national trends, many Vermonters struggle to find providers. Cory has seen this personally as he has struggled to help his young adult daughter locate a primary care provider, and it even took Cory about four years to find his current primary care practitioner that he likes after losing his previous provider. Several programs target ongoing healthcare provider shortages as well as ways to best distribute the existing healthcare workforce across the rural-majority state. The University of Vermont also tries to help recruit and train healthcare workers for the state.

“We know access is an important part of a healthy community. As an academic center in Burlington, we are training people as fast and at as high a level as we can with the thought if you come study in Vermont, you have a good chance of practicing in the state as well,” Cory explains.

This certainly seems to hold true as 2018 data from the Vermont Department of Health showed that 33% of practicing physicians in Vermont either attended medical school or completed a residency at the University of Vermont.

A Healthcare System on a Precipice

When considering Vermont’s healthcare challenges, Cory evokes what is often called the “iron triangle,” a visual representation of the relationship between quality, accessibility, and affordability in a healthcare system with fixed resources. Cory notes that Vermonters call this concept the “three-legged stool” to emphasize how all three components are needed for functionality. Within the bounds of either visual, increasing any one or two of the characteristics decreases the others. For example, prioritizing quality and accessibility pulls from affordability while allotting resources to higher quality reduces accessibility and affordability. This underlying tension exists in all health systems, and the solution to the iron triangle is akin to Gatsby’s green light for health policymakers.

“It goes back to Vermont’s limited population compared to other states. I don’t think we have a critical mass to sustain a healthcare system at the level [of quality] that Vermonters expect in terms of care,” Cory explains.

Simply allotting additional public funds to healthcare spending and therefore making the whole metaphorical triangle bigger is unfortunately not a painless solution. In 2021 Vermont state general tax revenues were approximately $14,000 per capita versus the national equivalent of $12,300. From 1991 to 2020 Vermont went from being in the lowest to the top 20% for per capita healthcare spending across states. Ultimately, it is not evident that Vermont is under-taxing residents or underspending on healthcare.

Despite high per capita healthcare spending, there are still gaping financial issues with Vermont’s healthcare system. In 2023, nine out of fourteen Vermont hospitals had a negative operating margin. Analysis from the KFF shows that on the 2024 health insurance exchange marketplace the average lowest cost silver plan premium was $948 in Vermont compared to $324 in neighboring New Hampshire or $468 nationally. Similarly, rates for individual and small group commercial insurance plans increased between 46% and 80% from their 2018 equivalent rates according to the Green Mountain Care Board. Another KFF study shows that Vermonter employer-based insurance premiums in 2022 were about $2,000 higher than the national average, although the employee contribution to premiums was about even with the national average.

“There is good care, and there are healthy Vermonters, [but] the bigger focus is the cost of that care. I feel we don’t have enough people to sustain the system, so we have a choice of funding the system at a government level or maybe not having everything available,” Cory notes. “We need more providers to have appropriate access but that will come at a cost too. Health in Vermont would be better if access was preserved but the tough part is [that] care has to be paid for at some point.”

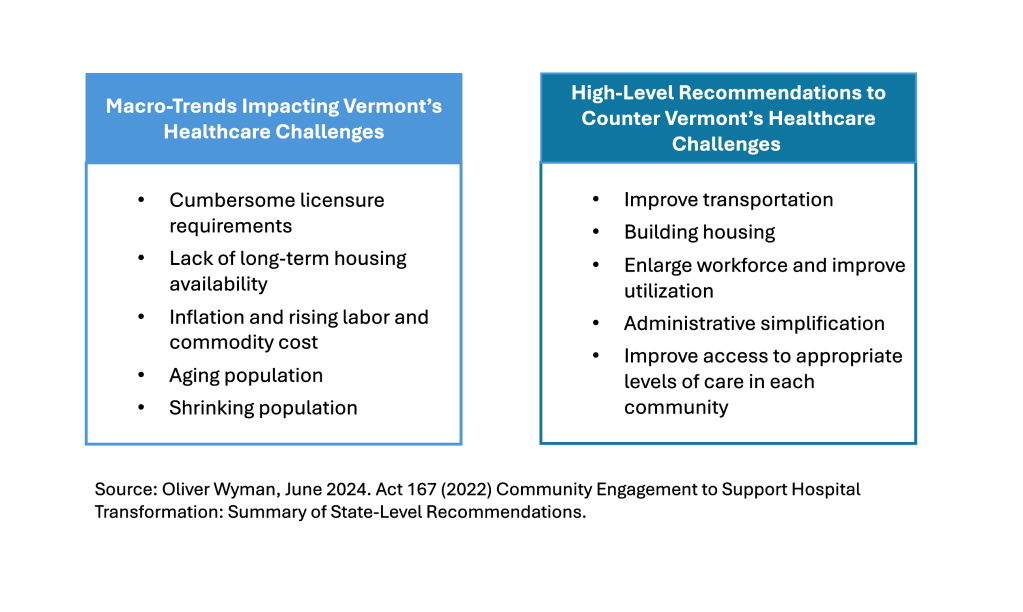

The current lack of affordability for patients and sustainability for hospitals demonstrates that something needs to give or key parts of Vermont’s health system may collapse. The state hired consultancy Oliver Wyman to evaluate state-wide hospital transformation. While the associated engagement has not yet concluded, an initial June 2024 report maps out the interconnected challenges plaguing providers, hospitals, and patients in Vermont, and provides a five year plan to address current system shortcomings. However, action items like build housing for the unhoused and healthcare workers recruited to Vermont are far from easy to complete in a timely and affordable manner. Vermont has a tough road ahead to figure out how it is going to address its very real healthcare needs.

Cory explains that much of the complexity in American healthcare is because changes to the healthcare system only add to the existing system but rarely remove anything. The resulting effect resembles either a holey patchwork quilt or Frankenstein’s monster.

“The United States healthcare system was not built with any plan in mind,” Cory describes. “It evolved over a hundred years, and we ended up with what we ended up with. We built on top of a machine to the point where the machine could not be taken apart.”

As the iron triangle creeps toward a breaking point in Vermont, the state will need to decide whether it wants to patch on another addition to the current system or if it will finally autopsy Frankenstein’s monster and build something fresh. Granted, with the heavy interplay between federal and state stakeholders in shaping healthcare programs and the need to provide continuous high quality, accessible, and affordable care to Vermonters all the while, either pathway will be daunting. Unfortunately, there is no easy answer for how to overhaul Vermont healthcare in support of long-term sustainability. Hopefully, the care for one’s neighbors that is abundant in the state will continue to drive decision-making until the triangle is balanced again.

Leave a comment