Interview with Gloria Burnett, Director of the Alaska Center for Rural Health

“There were a lot of things that made me see the need for a rural healthcare workforce from the patient perspective that I did not understand until I experienced it myself as a patient while pregnant.”

-Gloria Burnett

The Adventure of Alaska

Gloria Burnett moved to Alaska in search of adventure. She ended up in Utqiagvik, a whaling town on Alaska’s northern coast that abuts the Arctic Ocean, where polar bears are sometimes visible and the only way in or out of town is by plane.

At the time, Gloria had spent most of her life in Pennsylvania and wanted a life change after graduating with a master’s in education from Drexel University. A friend helped connect her with what was meant to be a summer position but stretched into five years at Iḷisaġvik College, Alaska’s only federally recognized tribal college.

“It is not an easy place to live. Not everyone is cut out for living in Alaska,” Gloria attests.

By geographic footprint, Alaska (population: 730,000) is by far the largest state in America. With its fifteen national parks and 120 state parks, Alaska has over 322 million acres of preserved public lands. The state stretches across wetlands, forests, mountains, and tundra as well as volcanoes and glaciers. While the geography fosters a connection to nature for residents, it also can be physically hostile and isolating.

The state’s expansiveness and climate also amplify typical challenges associated with rural healthcare delivery. Travel throughout the state is challenging, and at times downright impossible due to fog and storms. Alaskan winters feature a near total absence of sunlight while summers are oversaturated with lingering daylight, contributing to health challenges stemming from sleep disruption, seasonal affective disorder, and isolation.

To overcome the more taxing parts of life in the state, residents lean into local connections.

“There is a different sense of community in Utqiagvik, people are in it together. The friendships I made are lifelong and more like family because we had to rely on one another and support one another through winters and storms,” Gloria describes. “I have not experienced the sense of community in Alaska anywhere else.”

Utqiagvik: Close-Knit Community in the Tundra

Tucked up against the Arctic Ocean and more than 300 miles north of the Arctic Circle demarcation, Utqiagvik, Alaska (population: 5,000) is the northernmost community in the United States. About 65% of residents are Iñupiat. At the time of its creation in 1972, the North Slope Borough (population: 10,000), which governs Utqiagvik and surrounding villages, was the first Native American-controlled municipal government, at the forefront of the national indigenous self-determination movement.

Near the Iñupiat Heritage Center, a pair of jawbones from a bowhead whale tower over the frozen beach to form the “Gateway to the Arctic” and serve as a monument to whaling in the region. While commercial whaling is no longer permitted in the area due to its negative ecological impact, the local Iñupiat continue to practice subsistence whaling as part of cultural preservation efforts.

Iḷisaġvik College is about as removed from the stereotypical American college as possible. The North Slope Borough founded the school to help residents pursue higher education at an “unapologetically Iñupiaq” institution. While students can complete a Iñupiaq Studies program or take Iñupiaq language classes, this mission flows across every facet of campus life. Indigenous knowledge is integrated across disciplines, one example being that health-minded students can study the traditional knowledge of arctic plants, including medical applications of tundra plants. Elders also take courses and serve as guest contributors, leaning into a multi-generational education model.

“Whenever we could incorporate the local community, those were always my favorite parts of teaching, integrating with the community and learning from the community,” Gloria reflects. “We frequently invited Elders to join in classes as an Elder-student, acting as both a student and support. I enjoyed hearing Elders connect and inspire students to pursue healthcare careers since the need for healthcare providers in Utqiagvik is so great, and the Elders want to see those roles filled with local community members.”

As Allied Health Coordinator at Iḷisaġvik, Gloria advised students exploring healthcare careers, taught psychology-adjacent courses, and identified ways for the school to collaborate with ongoing efforts to alleviate healthcare provider shortages in the area, including those of partner Area Health Education Centers (AHEC). Alaska’s AHEC supports efforts to combat healthcare workforce shortages, especially in rural and underserved communities, by supporting retention of the existing workforce and healthcare education opportunities for students.

As many of Gloria’s students went on to pursue healthcare careers, including as registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, and counselors, she witnessed firsthand the value of training the next generation of healthcare providers locally.

Self-Determination in Alaska Native Healthcare

Healthcare coordination in the Arctic is complicated. To better understand how tribal health systems layer onto services for the Iñupiaq community of Utqiagvik, Gloria referred me to April Kyle’s 2023 keynote address at the Alaska State of Reform Conference. April is the President and CEO of the Southcentral Foundation, one of the organizations managing care delivery within the Alaska Native Health System.

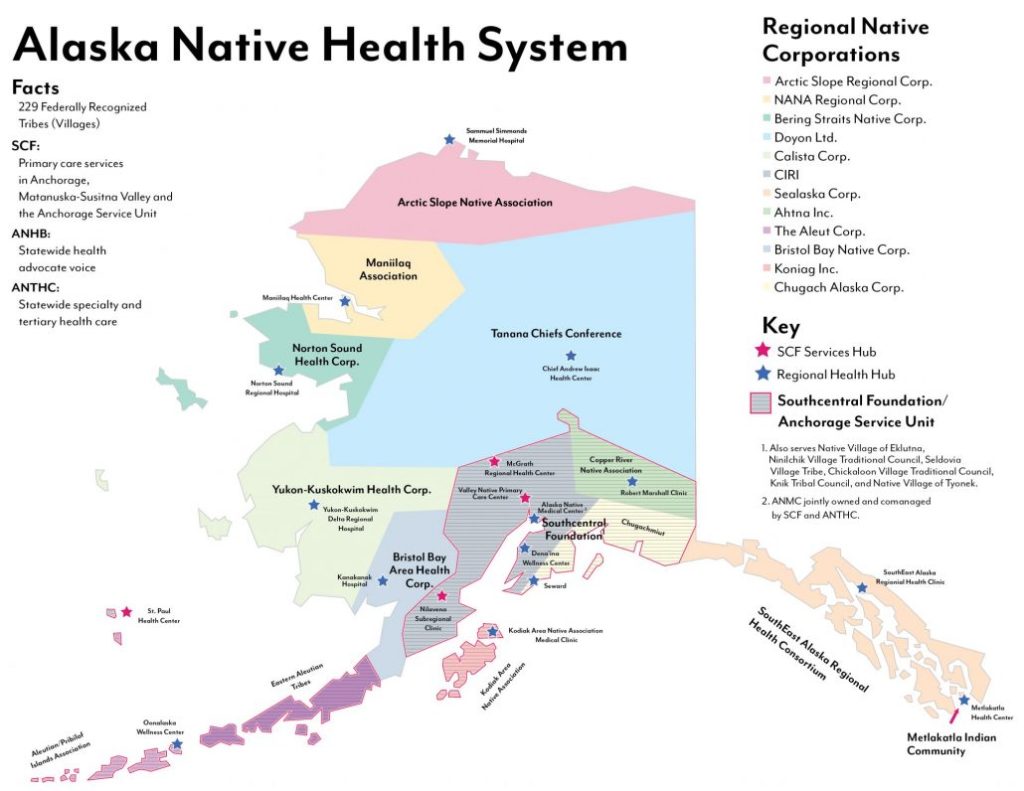

Source: Southcentral Foundation, Who We Serve, “Alaska Native Health System.” August 2019.

In her address, April shared some of the history of Alaska Native healthcare delivery, starting with the 1955 creation of the Indian Health Service (IHS).

“When I was a kid [IHS] was the place you went when you did not have insurance and could not afford to go somewhere else,” April recounts. “It felt to us as a family as the second-class place to go… [It was an] underfunded system that had no way to keep up with the needs of the population.”

The Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 disrupted the existing system, allocating the IHS budget to tribal entities to contract their own healthcare services. The new model of care in Alaska, managed by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, leverages a hub and spoke model with regional and community centers spinning out from the central Anchorage hospital hub. Case Manager Supports, who themselves are members of Alaska Native communities, act as accessible contacts for patients and help coordinate care, with a focus on promoting holistic care and wellness.

“The tribal health system in Alaska is this amazing demonstration of what it can look like when the community has the opportunity to design something that can be meaningful to its families and its people,” April explains. “Through self-determination, the local design of healthcare is able to best meet the needs of the people and communities in its area.”

Arctic Healthcare Delivery

Many essential healthcare services are not physically available in Utqiagvik. Far before the Covid-19 pandemic, the tribal health system leveraged telemedicine to make health assessments and triage patients. While some specialist clinics come to the area on a rotating schedule, in many urgent health situations patients must travel to receive care.

“It is exasperating to navigate this extra layer of travel and determine whether specialty clinics are available in a certain time frame and whether that will work with your time frame and then getting preauthorization for travel,” Gloria attests.

Working in healthcare workforce efforts, Gloria knew many of the challenges associated with healthcare delivery in Utqiagvik, but experiencing two pregnancies shifted her understanding of the paradigm.

“I was living on the North Slope when I had both my children, so I really got to see what the rural health experience was like by being pregnant in a place where I had to leave the community to access healthcare,” she explains.

Small critical access hospital Samuel Simmonds Memorial Hospital is operated by the Arctic Slope Native Association in Utqiagvik. Based on how the broader IHS funding flows, care can typically only be accessed by individuals enrolled as members of a federally recognized tribe, and it is usually prohibitively expensive for non-native residents to be treated at the hospital. Due to this constraint, Gloria received medical care for her pregnancies from a local private practice nurse practitioner and flew to a hospital in Anchorage over 700 miles away for milestone appointments as needed.

Regardless of tribal affiliation, many expectant parents in Utqiagvik must navigate leaving the community as Samuel Simmonds does not have a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Gloria notes that the decision to deliver at a hospital with a NICU can be informed by risk assessment, personal preference, and clinician guidance. Logistically, relocation during pregnancy is challenging. For Gloria’s pregnancies, she moved to Anchorage a month before her due date, delivered in the Anchorage hospital, and then stayed there after birth for monitoring before returning home to Utqiagvik. During this time, she had to pay for housing in Anchorage in addition to covering her housing costs in Utqiagvik.

“There were a lot of things that made me see the need for a rural healthcare workforce from the patient perspective that I did not understand until I experienced it myself as a patient,” she recalls. “You learn a lot more by going through it and dealing with those extra stresses beyond becoming a mom for the first time.”

Building Up a Rural Healthcare Workforce

While healthcare education anchored Gloria to Utqiagvik initially, ultimately the healthcare system was the catalyst for her departure.

“As a new mom, I knew that I did not want to stay in Utqiagvik with that level of healthcare service with young ones,” she explains.

With a newborn and toddler, Gloria relocated her family to Anchorage, taking the role of Director of the Alaska Center for Rural Health and Health Workforce with Alaska’s AHEC at the University of Alaska Anchorage. For the past ten years she has led the program that once collaborated with her through grants at Iḷisaġvik College.

“My focus has always been on the healthcare workforce and I think as a state, increasing access to healthcare by having a stronger healthcare workforce that is not stretched so thin and so reliant on itinerant providers would improve health access for many Alaskans in turn, improving the health of Alaskans,” she advocates.

Gloria’s story highlights the tangible impacts of healthcare deserts. When there is not sufficient healthcare access in areas, the people that can relocate are pushed to leave communities and geographies that they love in search of more stable infrastructure for their families. While conditions in Utqiagvik and other arctic communities are more extreme than much of rural America, growing shortages of healthcare providers continue to serve as a bellwether for impending challenges nationally. There is a crucial need for healthcare workforce activation and expansion, especially to meet the needs of rural communities.

So how can a state grow its healthcare workforce in pursuit of solving this wider issue?

“In Alaska we need to better promote the unique assets of living in our state to attract more people to the existing healthcare jobs,” Gloria explains. “Growing our own professionals is a long-term strategy, but we also have to consider innovations in recruitment and retention to address these challenges in the short-term.”

As Gloria noted, Alaska is not for everyone. For the right healthcare workers interested in making the move to the vast, rugged state, hopefully the thought of delivering care in a place where the sun either does not rise or does not set for much of the year and residents counter frigid winters with the warmth of community connections is appealing. To those who might be the best fit, it will sound like an adventure.

Leave a comment