Interview with Caleb Diaz, Medical Student, Former Hospital Consultant

“I saw from the administrative perspective how challenging it is for patients to find care. I think a lot of physicians are restrictive of what insurance they accept, which bars folks from getting good quality care, but there is financial motive from the physician perspective. As a future provider, I will have to think about these things going forward, but I have seen how brutal it is to navigate this healthcare system.”

– Caleb Diaz

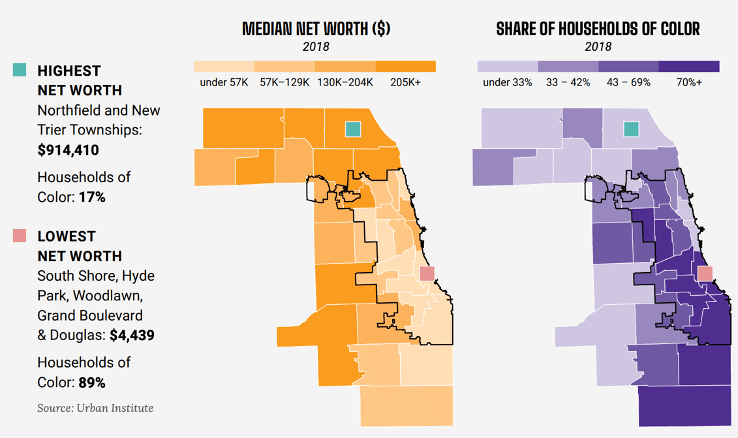

Chicago: A Tale of Two Cities and the Social Determinants of Health

Caleb Diaz is at an inflection point in his career. After earning an economics degree from the University of Pennsylvania and consulting for hospitals for three years, Caleb is starting medical school at the University of Chicago in his beloved hometown.

Hearing about his mom’s experiences as an ICU nurse in the city piqued Caleb’s interest in healthcare, but he was particularly fascinated by her account of healthcare challenges that seemed systemic in nature. Early in college he plotted out a pathway to a PhD in medical sociology or health economics, but initial experiences with research led him to realize his goals for career impact were incompatible with academia. With his economic degree in hand, he took a position in consulting back in Chicago right as the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted typical life.

Chicago (population: 2.7 million) is the third most populous city in America. The Midwestern city’s location on Lake Michigan secures its signature moderate summers and snow-heavy winters. It was formally incorporated in 1837, but much of its initial growth and physical construction lasted through the 1920s, cultivating the feel of a city that is younger than its peer cities in the northeast but still steeped in history and character.

“Culturally Chicago folks are a bit rough around the edges but are typically kinder than people from New York or Philadelphia. The ‘get a drink from your local bar after work’ vibe exists and communal love of where you come from is very big here,” Caleb reflects. “I’m evidence that people from Chicago love Chicago and talk about it all the time.”

Caleb also understands that where you live in Chicago matters.

“At a systems level, Chicago is a split city. It is honestly two different cities between the North Side and South Side,” he describes.

On a light-hearted level, this division is depicted through team affiliation to the North Side’s Cubs or the South Side’s White Sox. More substantively, this divide feeds into almost every one of the social determinants of health.

While no area of the city is homogeneous, the North Side is an affluent area of town with a predominantly white population. The South Side once hosted most of the city’s manufacturing capabilities, but the demise of the local steel industry and other manufacturing has left a lot of the factories in disrepair, contributing to locally-based environmental waste. Neighborhoods in the South Side have hosted a predominantly Black population since the Great Migration when Black families from rural southern states moved to northern urban centers in the 20th century.

Data Source: Urban Institute, 2018. Graphic Source: “Cook County has stark differences in wealth.” We Will Chicago, Economic Development, Draft for Public Input from the Office of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, July 2022.

The social determinants of health (SDOH) are all the non-medical factors that influence a person’s health, including access to housing, access to nutritious food, and access to safe, non-polluted outdoor space for exercise and leisure activities. SDOH can nourish or starve holistic health, and they often drive many chronic medical conditions (e.g., T2 diabetes, heart disease) alongside biology.

“Further northeast where you line the lake, it is beautiful and clean. You have access to a natural running trail, and it is just a healthier part of the city,” Caleb describes. “When you contrast that to the South Side where the air is polluted, and there are no natural places to go to exercise and be outside, it has an adverse impact on someone’s health. The other part is gun violence. In parts of the city, you could go outside, and your life could be in danger from gun violence. All these factors impact a person’s health as well as [the prevalence of] food deserts.”

Amidst its divisions, Chicago is also a medical research hub, with the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and Rush University each acting as Centers of Excellence in their respective specialty areas.

“Having these great institutions active in medical research all over the city is incredible. Chicago hospitals rival a lot of other cities in the country,” Caleb shares.

Northwestern is in the North Side, University of Chicago in the South Side, and Rush sits near the Loop (fellow tourists: this is where they keep the Bean) between the north/south divide.

“At the University of Chicago’s trauma center, gunshot wounds and stabbings are the number one thing they see,” Caleb recounts. “It is very untypical to see that level of violence at a hospital trauma center; typically, motor vehicle accidents are number one. Chicago is a city, so you see [everything] in general, but if I were studying at Northwestern, I would not expect to see that as much.”

Source: “Chicago Gun Violence by Neighborhood,” The Illinois Policy Institute. August 10, 2023.

Illinois: Violet-Blue State in the Midwest

Illinois (population: 12.6 million) sometimes seems to take the backseat to Chicago, at least to Chicagoans.

“If Chicago was not here, we would be Indiana,” Caleb jokes. “People’s perceptions of the Midwest are kind of spot on. Illinois is Chicago and then everything else feels suburban or rural.”

Caleb emphasizes that Illinois is not a liberal monolith. Like in many states, there is a tension between the urban liberalism and rural conservatism within the state and even the purple leanings of the wealthy Chicagoland suburbs.

In healthcare, the political leanings of the Midwest have recently been under a brighter spotlight following the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson decision that negated the previous federal right to abortion secured by the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

While Illinois may not be fully blue, it certainly seems so compared to its more conservative neighbors in the Midwest Heartland, leading to the rise of its identity as a reproductive health safe harbor. NPR reports that in June 2023 abortions in Illinois increased 45% from April 2022 due to an influx of patients traveling from states that outlawed abortion.

Indiana University’s medical school now sends their obstetrics residents to Illinois to train in abortion care since it is almost entirely banned in Indiana. They do not disclose which Illinois sites they partner with due to security concerns, which have been plentiful. One of the physicians who trains residents in the program was investigated by Indiana’s attorney general after she provided a legal abortion to a ten-year old rape victim who had traveled from Ohio for the procedure shortly after the Dobbs decision. The case and resulting media coverage made the physician a public target for anti-abortion activists.

“Policies that are being spread around and passed in the Midwest affect Chicago and Illinois because it is the bluest state out of the Midwest,” Caleb explains. “You get a lot of folks coming in because of adverse policies affecting them in other states.”

Hospital Oversight in the Time of Managed Care

As a consultant, Caleb witnessed firsthand how financial levers tangibly impact care delivery in hospitals in Chicago and across the country. Armed with datasets, his team aimed to improve hospital care management and minimize clinical variation with the overarching goal of promoting cost savings.

Insurance, including Medicare, often pays hospitals for inpatient care with a lump sum reimbursement. This differs from the fee-for-service model typical in outpatient where each individual part of care is billed. Because of this, hospitals are incentivized to be cost conscious and manage cost of care. One main way hospitals manage cost of care is by monitoring patient length of stay.

“[Lowering patient length of stay] is primarily financially driven since every extra day the patient stays in the hospital is extra cost for the hospital, [but] there are some quality metrics [that show] that the longer the patient is in the hospital, the worse the outcomes,” Caleb explains.

While quick discharges are a win-win when viewed through cost and quality lenses, clinicians and patients alike might bristle at the thought of reimbursement design informing clinical care too extensively.

“Where physicians and administrators collide is that physicians think they are doing what is in the best interest of patients, which is generally true, but there are ways they can also save money in the long run,” Caleb explains.

The other main part of Caleb’s consulting work was evaluating clinical variation to ensure that physicians within a hospital were following standard clinical practice.

Unsurprisingly, physicians do not like being told how to practice medicine, especially from non-clinician consultants. Still, as evidence evolves, providers should be willing to adjust practices if they want to provide patients with top quality, evidence-backed care. However, some clinicians may not see it that way.

“I noticed that physicians are really bad statisticians sometimes,” Caleb recounts. “They have all this anecdotal evidence that supports their claim but [as consultants] we were coming in with tens of thousands of observations of care… It was interesting to have physicians fight with anecdotal evidence versus backed big data that shows that what they were doing was not the best thing or standard practice.”

Ultimately, one of the secrets of healthcare is that clinicians and administrators alike are human. Both parties naturally may implicitly weight personal experience more heavily than data when making judgments at times. However, in a world of increasingly standardized medicine and active managed care, the extent to which clinicians can freely deviate from recommendations may be narrowing. This is a relatively newer phenomenon.

“In the past twenty years oversight has increased thanks to managed care insurance companies and [hospitals] holding physicians accountable for the things that they are doing,” Caleb explains. “That is why physicians say that the heyday of being a physician is over. There is a lot more paperwork now, and physicians also do not like being told that what they are doing is not standard.”

Public Health and Medicine: Beyond the Status Quo

In many ways medical school is a brand-new challenge for Caleb. However, as he begins his formal clinical training, he arrives with a foundational understanding of the many factors affecting health and healthcare beyond medicine itself.

It is impossible to disentangle medicine from the intricate spiderweb of how healthcare is paid for in the United States. Caleb knows better than most that funding informs healthcare access.

“I saw from the administrative perspective how challenging it is for patients to find care,” Caleb reflects. “I think a lot of physicians are restrictive of what insurance they accept, which bars folks from getting good quality care, but there is financial motive from the physician perspective. As a future provider, I will have to think about these things going forward, but I have seen how brutal it is to navigate this healthcare system.”

Having seen healthcare delivery across a wide range of American hospitals, Caleb also can confirm that Chicago is not alone in its socially-driven health needs.

“In tiny rural towns in the south some of the main health issues, like congestive heart failure and obesity, are associated with poverty and food deserts,” he recounts. “These same issues exist in a large pocket of Chicago but are not endemic to Chicago. These are problems that exist throughout the country [and] have solutions in public health.”

Medicine may be one of the few industries where physicians (or future physicians in Caleb’s case) would like to reduce demand on their services. Systemic health inequities contribute to poor health outcomes which require downstream medical intervention. Public health interventions provide the opportunity to prevent disease. The more that the next generation of physicians engages with public health, the better.

The Hippocratic Oath was developed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC and includes some points that may be culturally outdated, including a vow to never conduct surgery (then viewed as a separate profession) or seduce anyone while visiting a sick patient (now typically implied without a formal vow). Some medical schools have nixed the practice of a formal oath, while others use modern adaptations. However, the most famous line from the oath, which is a version of “I will do no harm to my patients,” is timeless.

When medicine and public health team up, that “do no harm” mentality can aspire to a greater sense of doing good and fixing lingering problems alongside the acute.

Ultimately it is this kind of outlook that might eventually lead to a future version of Chicago where rooting for the White Sox or the Cubs is not associated with a person’s health outcomes because of geographically-based health inequities.

Leave a comment