Interview with Melissa Ugland, Public Health Advisor, Adjunct Professor

“We know that Medicaid expansion improves health, stabilizes hospital finances, and keeps people more secure in their jobs. There is this cascade of health and economic benefits that comes from Medicaid expansion, so the fact that we are one of the ten states that has not expanded means that Wisconsin pays a price.”

– Melissa Ugland

Pandemic Preparedness Needs Public Health Funding

Melissa Ugland knows that health could be better in Wisconsin (population: 5.9M). Drawing from her twenty-year career in public health, she identifies two areas where the state struggles most: 1) low public health funding, and 2) lack of Medicaid expansion.

According to America’s Health Rankings from the UnitedHealth Foundation, Wisconsin tied for last with Michigan in 2022 for the lowest per capita public health funding in the United States with $128 spent per resident annually. Melissa notes that the lack of funding hinders the state’s infectious disease efforts.

“Wisconsin is incredibly poorly positioned to handle another pandemic. We have wonderful people working in public health here, but we are going to have a hard time if there is something similar to the COVID-19 pandemic in the future,” Melissa assesses.

Melissa is well-equipped to assess the state’s preparedness to handle infectious diseases. Along with a business partner, she served as a public health consultant to manage public health efforts for workplace safety for Milwaukee County during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. She also personally experienced a lab-confirmed case of mumps in 2005 during an outbreak and saw firsthand how providers were unsure of appropriate safety protocols due to the rarity of the infectious disease.

“What was strange was that nobody I saw knew what I had was mumps since it is nearly eradicated,” she recalls. “It is a testament to vaccine success. We are starting to see this come up with measles too where providers do not know how to diagnose it or how incredibly contagious it is.”

Public Health from Thailand to Wisconsin

Despite her Midwest roots, Melissa fell in love with public health across the world. After growing up in South Minneapolis, she moved to the East Coast to attend college at Boston University. She studied abroad during her junior year in Niger where she met a professor connected to the Peace Corps who inspired Melissa to join the program. She spent two years with the Peace Corps in rural Thailand engaging with local health education efforts through schools.

“Like most young people, I took my good health for granted. Being in a place where it is easy to not only become sick but maybe not have access to medicine or health providers was a reality check,” Melissa recounts. “Getting equitable access to treatment for chronic conditions or vaccines globally is something that we are nowhere near.”

After her Peace Corps term, she earned a Master of Public Health at the University of Minnesota, focusing on child and maternal health (note: she does not recommend taking the GRE in Thailand after not speaking English for over a year).

Eventually Melissa and her husband moved to Milwaukee (population: 560,000), Wisconsin’s largest city, after he began a teaching position at Marquette University. They settled in the suburbs of the Lake Michigan-adjacent city, just a 90-minute drive north of Chicago. Melissa embarked on a career in public health education, grant writing, and consulting for academic, community, and nonprofit organizations scattered throughout the Milwaukee County area (population: 916,000).

An Abbreviated History of the ACA, Medicaid Expansion, and Wisconsin

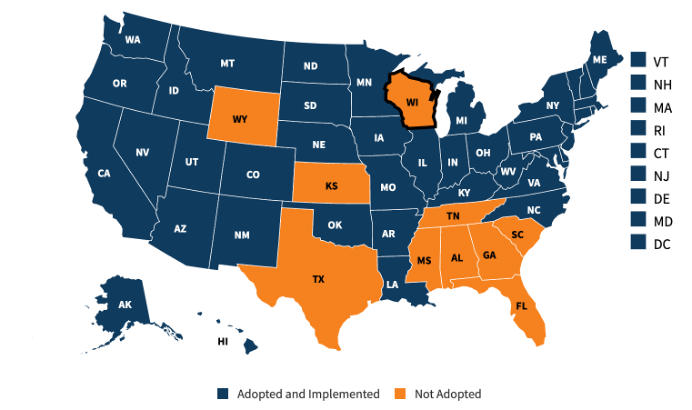

More than a decade after the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s implementation, Wisconsin is one of the ten states that has not adopted Medicaid expansion.

Source: “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 2024.

“We know that Medicaid expansion improves health, stabilizes hospital finances, and keeps people more secure in their jobs. There is this cascade of health and economic benefits that comes from Medicaid expansion, so the fact that we are one of the ten states that has not expanded means that Wisconsin pays a price,” Melissa reflects.

Medicaid is funded jointly by the federal government and states. States create and administer their respective Medicaid programs based on federal guidelines. The ACA adjusted Medicaid eligibility to provide public health coverage for adults under 65 who earn below 138% of the federal poverty line. Before the ACA, only certain low-income, nondisabled adults were eligible for Medicaid nationally – primarily pregnant women and adults with dependent children.

The ACA stipulated that the federal government fund almost all the costs associated with expanding Medicaid eligibility. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the federal government previously funded 50-78% of Medicaid costs, making this a significant influx of resources.

A 2012 Supreme Court decision blocked national Medicaid expansion, ruling that states should decide whether to adopt the enhanced program and its increased coverage.

As quadrennially highlighted on the presidential campaign trail, Wisconsin is a swing state. In the past three presidential elections, Wisconsin voters have selected the election victor with a less than 1% margin. Like every state except Maine and Nebraska, all of Wisconsin’s electoral votes are cast for their election winner regardless of the closeness of the race, elevating it and other swing states to their national prominence as they ultimately determine electoral outcomes.

A decade-long impasse on Medicaid expansion may be one side effect of Wisconsin’s politically purple landscape. While Democrat Governor Tony Evers has pushed for Medicaid expansion, the Republican-majority state legislature has repeatedly blocked the proposal.

The Wisconsin Department of Health notes that expanding Wisconsin’s Medicaid program, which operates under the moniker BadgerCare, would extend coverage to approximately ninety thousand Wisconsinites and generate $1.6 billion in savings for the state.

“Medicaid expansion is the biggest thing that needs to happen to improve health in Wisconsin,” Melissa assesses.

Integrating Health, Caring for All

For the uninsured or underinsured in America, getting access to essential healthcare services is challenging. Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) serve as a safety net. FQHCs are nonprofit health clinics that provide primary care for patients regardless of their ability to pay, typically relying on a mix of federal funds and private donations.

The Gerald L Ignace Indian Health Center, located in Milwaukee’s diverse Near South Side neighborhood, is Wisconsin’s only urban Indian health center and a FQHC. The center’s core mission is to support the health of the local Native American population, but it also treats patients of all backgrounds. Melissa serves as the Center’s Public Health Advisor.

“We serve everybody regardless of insurance, income, or other factors. We mostly serve people who live nearby who experience various social drivers of health like racism, financial insecurity, and housing insecurity. We have a lot of life situations that show up in our clinic that do not necessarily result in a clinical diagnosis,” Melissa describes.

The Center addresses these needs in a remodeled building that previously was a department store. The site includes a medical clinic, pharmacy, dental clinical, behavioral health clinic, and physical therapist-staffed fitness center. Insurance navigators help patients connect to coverage and even enroll in Medicaid if eligible. Melissa brings public health into the clinic through educational and advocacy programming.

“There is a real hands-on prevention and education approach because most people do not find it easy to navigate healthcare. They want to make good decisions and are not always sure who to believe or how to get information, so if you can go to a place where you feel comfortable and connected and get some questions answered and maybe even go right downstairs to make an appointment – all the better,” Melissa explains.

Nationally, the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted Native American communities. The National Institute of Health reports that Native Americans experienced over three times higher the age-adjusted rate of hospitalizations and double the fatalities of non-Hispanic whites. In response, the Center rolled out an early vaccination campaign with vaccines provided by the Indian Health Service. Melissa notes that consequently Native Americans had the highest vaccination rates of any racial group in the county for a time.

“The vaccines were so scarce, and it was scary. COVID-19 was wiping out whole generations of Native American families and some of the only fluent speakers of some native languages. We had a line around the block and people drove in from beyond Wisconsin. Then for months and months there were zero deaths from COVID-19 documented in the county’s Native American community,” she recounts.

The Public Health of Wisconsin Beer Culture

Wisconsin has produced many notable exports over the years: motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson, avowed anti-communist Senator Joseph McCarthy, and architect Frank Lloyd Wright and his Prairie Style.

However, the state is best known nationally for its dairy and beer production. The Wisconsin dairy industry catalyzed the tradition of Green Bay Packers fans wearing foam cheese wedge hats and popularized cheese curds as a beloved snack. The beer industry has arguably had an even greater impact on the local culture.

“If you are ten years old and at a bar with your parents you can legally get a beer in Wisconsin. People like to say it is because there are so many Germans here but whatever it is, it is strange if you are not from here,” Melissa explains. “Obviously alcohol is not good for you. We have lots of drunk driving and repeat drunk driving.”

In the 19th Century, large groups of German immigrants moved to Wisconsin for agricultural opportunities, establishing beer brewing as a local mainstay. According to the 2023 American Community Survey, 35% of Wisconsinites self-identify as having German ancestry. While the drinking age technically remains twenty-one, anyone underage can consume alcohol when accompanied by a parent – there is no minimum age for this.

According to the University of Wisconsin’s 2024 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps Report, 25% of Wisconsinites self-report as excessive drinkers. Based on the latest 2021 CDC data, the state has the highest rates of binge-drinking in the country. All seventy-two Wisconsin counties have an excessive drinking rate of at least 20%.

It is likely not a coincidence that Wisconsin is also the only state where first time drunk driving offenses are not treated as a criminal offense but rather as a civil offense. First time drunk drivers may face a fine as low as $150 in conjunction with a six-month license suspension. According to the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, 35% of all fatal crashes in Wisconsin in 2022 occurred while a driver was impaired from alcohol or other substances.

“I have been told that the Tavern League of Wisconsin is the strongest lobbying group of its kind,” Melissa shares.

The Tavern League of Wisconsin, a nonprofit trade association, was founded in 1935 shortly after the end of prohibition and now represents over five thousand alcohol vendors. It is the largest trade association for alcohol retailers in the country. A 2023 Marquette Law Review article by Noah Wolfenstein details more about the role of lobbying in shaping Wisconsin’s drunk driving laws.

A Public Health Workforce Under Pressure

A 2024 study from the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Melissa’s beloved alma mater, found that America’s public health workforce experienced a ~40% decrease from 1980 to 2014. The study notes that 2021 survey data indicates that between a third to a half of public health employees working for the government were considering leaving the field by 2026, with stress and burnout cited as key drivers. This compounds an existing shortage of public health workers from 2017 to 2019 when ~80,000 full time employee positions at health departments were vacant.

Unfortunately, the infectious disease landscape is unlikely to easily accommodate a leaner workforce.

“We are likely to see similar viral threats to COVID-19 emerge now that it is endemic,” Melissa explains. “We have seen spillover of COVID-19 fatigue – we are seeing decreased vaccination rates across the board, so we are now up against that threat. It is very hard to know how to address that without added resources.”

A 2024 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study found that Wisconsin trails national childhood immunization rates for kids entering kindergarten, with only 85% of Wisconsin children receiving the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination compared to the national average of 93%. Similarly, only 86% of Wisconsin kindergartners received the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccine and polio vaccines.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, America maintained a 95% immunization rate for MMR and similar childhood immunizations in recent years. According to the World Health Organization, a 95% immunization rate for measles is the approximate threshold to achieve herd immunity.

“Everyone benefits from public health, but greater investment in it would extend health, life, and economic security for so many more,” Melissa concludes.

Leave a comment