Interview with Dr. Robert Califf, Former FDA Commissioner, Cardiologist, Researcher, Professor

“The FDA Commissioner is a buffer between the political and civil service worlds. In practice, the FDA is more like a referee than anything else, calling the shots from a set of rules and laws and not making it up as it goes along. We want people who do not have a financial conflict of interest making those calls – that is what the civil service is.”

– Dr. Robert Califf

The Innovation Golden Age

Dr. Robert Califf entered medicine at the dawn of a research and innovation golden age. Credited with over 1,300 peer-reviewed publications and awarded some of medicine’s top honors, he was hardly a passive participant.

Despite having received two separate presidential appointments, Robert still considers captaining his high school basketball team to win the 1969 South Carolina state championship as the peak excitement of his life. As an undergrad at Duke in Durham, North Carolina, he felt drawn to clinical psychology but summers interning in state prisons disabused him of that career and led him to medicine.

When Robert returned to Duke for medical school in 1974, the popularized Holter monitor, a wearable device resembling an iPod Nano on a lanyard, made around the clock heart function monitoring accessible. At the time, Robert recalls, 30% of patients who experienced a heart attack and made it to the hospital died within 30 days, and the leading cause of death was sudden death from a heart attack. Duke’s medical curriculum uniquely included a year of research, allowing Robert to work on a study to predict which patients were predisposed to sudden death from a heart attack.

After graduating medical school in 1978, Robert began an internal medicine residency at the University of California, San Francisco. In 1980, he returned to Duke to complete a cardiology fellowship. That year, physicians connected that an angiogram showed blood clots in the coronary artery when people had heart attacks. This breakthrough opened the door for a cascade of interventional exploration.

“Before the angiogram, we did not know how heart attacks worked. After the angiogram, we had a target and something we could intervene on to improve patient outcomes. Fairly early in my career I was caring for people who were critically ill, and I also started doing research to develop effective therapies,” Robert recounts.

While most of his early career was anchored to Duke’s medical ecosystem, Robert’s time in San Francisco also proved equally impactful.

“We ended up with a group of young people who had been interns together in San Francisco who were now scattered across the United States, and we began to work together on clinical trials,” he explains. “At Duke we had computational capabilities that did not exist in many places, so we coordinated the data for these clinical trials there, but it literally was a group of friends driven to do something about the clinical problems we saw.”

The result was that Robert launched a bicoastal career in two of the biggest hubs for biomedical innovation in the world: San Francisco’s Biotech Bay and North Carolina’s Research Triangle.

Robert’s research cohort started clinical trials for clot busters, which are medicines that dissolve blood clots to prevent heart attack and stroke, and then moved on to percutaneous cardiac interventions.

“Many of my friends were among the early interventional cardiologists using catheters to open arteries. There was a lot learned during that time. We tried interventions that looked really good in animal models, and while most of them did not work in people, we found a few that worked well,” Robert shares. “It was not due to me or our small group, but due to a global collaboration that included us, your risk of dying from a heart attack is cut in half today from what it was then in the 1970s because of these interventions. And they keep getting better.”

After his group completed small trials, they began to expand, ultimately moving to a multi-national model that enrolled tens of thousands of people in their clinical trials.

Naturally, cutting-edge clinical research relied on equally impressive technology. As the internet did not yet exist as a public utility, the technology that enabled Robert’s early clinical trials was the fax machine.

“People all over the world had fax machines, so if someone rolled into the ER with a heart attack, we would look at their EKG from a fax in a central location,” he recounts.

Robert continued to treat patients in the ICU and developed an outpatient clinic at Duke, while also continuing clinical trials.

“It seemed to me if the clinical trial approach we developed worked in cardiology, it ought to work in other areas, so we started the Duke Clinical Research Institute, which became a very large organization with 18 different specialties doing clinical trials using the infrastructure that we developed. It does not matter if it is psychology or hypertension or cancer, you need study design, computing, and high quality analysis. A lot of our trials ended up as the basis for FDA labeling – that led to a lot of interactions with the FDA and global regulators.”

The United States Food and Drug Administration

Fast-forward several decades, and in 2015 FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg let Robert know she would be leaving her appointment after a lengthy six years of service. She told him that he should be the next commissioner, contingent on the presidential appointment. Robert left Duke to work at the FDA as the Head of Medical Products and Tobacco. Then he got the call.

“President Obama asked me to be Commissioner and that was just great, but on my way out of the Oval Office, there was a whole team of people that reminded me that the President can offer you the job, but you are not the Commissioner until the Senate confirms you,” he recounts.

Robert was confirmed as the FDA Commissioner in February 2016, with bipartisan support in an 89-4 vote. He served until President Trump took office in January 2017.

“The FDA’s role is to make sure products on the market have a positive balance of safety and effectiveness, and when something that is a game changer comes along, like the anti-obesity medicines, that it gets moved along,” Robert outlines.

While the FDA Commissioner is appointed by the President, the organization itself is meant to be impartial and nonpartisan.

“Historically, 90% or more of the FDA’s work looks exactly the same regardless of the political administration,” Robert explains.

“The FDA Commissioner is a buffer between the political and civil service worlds. In practice, the FDA is more like a referee than anything else, calling the shots from a set of rules and laws and not making it up as it goes along. We want people who do not have a financial conflict of interest making those calls – that is what the civil service is.”

“Like all referees, the FDA has to make decisions independently, and it is complicated,” he assesses. “There is real reason to worry about bias caused by excess empathy for patients and companies beyond the scientific standard. For example, there is reason to be worried about excess empathy if someone came up with an ALS treatment where there is currently no effective treatment for a terrible disease, and the FDA has worked with the company for five years to get to the point where they are ready to submit their application. Everyone would hope that the treatment would work. But we have good internal mechanisms at the FDA and so many people involved that it is hard to imagine a scenario where one person could ‘throw the game’ so to speak because other people would see it.”

The Research Triangle, Biotech Bay, and the Road Back to the FDA

Following his first term at the FDA, Robert took two concurrent positions at Duke in Durham and at Google’s parent company Alphabet in San Francisco. During this time, he alternated between coasts for two-week stints before eventually settling at Alphabet full-time.

At Duke, Robert worked on operationalizing the new Duke Forge, a health data science research center. When Robert moved to Durham (population: 296,000) for college in 1970, he could smell the tobacco stored in the city’s downtown warehouses. By the time he had returned in 2017, those warehouses were biotech offices. Together with nearby Raleigh (population: 482,000) and Chapel Hill (population: 62,000), Durham makes up the Research Triangle and has bloomed as a biomedical innovation hub, earning its nickname as the “City of Medicine.” With its gothic campus architecture, basketball powerhouse, and randomly enough a zoology center boasting the most lemurs outside of Madagascar (which by the way is where the children’s PBS show Zoboomafoo was filmed), Duke is also unlike any other research locale.

At Alphabet, Robert led health strategy and policy efforts for Google Health and Google’s life sciences research company Verily. In San Francisco (population: 809,000), he and his wife lived in the Presidio (population: 3,000), the former site of an 18th Century Spanish military outpost that now encompasses a national park site with 75,000 trees, Lucasfilm’s headquarters (complete with a regal Yoda fountain), and a 20th Century palace façade modeled after Roman ruins, all adjacent to the Golden Gate Bridge. San Francisco claims the status of the birthplace of biotech, pinpointed to the creation of juggernaut Genentech in 1976. The city continues to be one of the top biotech hubs in the world, leveraging its proximity to key research universities and Silicon Valley.

“I had no intention of going back to the FDA. It is not that I did not like it, but Commissioner is something you usually do once,” Robert recounts. “I had a great job at Alphabet, but the Biden Administration was having trouble getting someone to take the job because it is so stressful and death threats come with the job and it has a low salary compared to similar work elsewhere. So they called me, and against the wishes of my family I agreed to do it – my family had had enough the first time.”

Robert was confirmed as the FDA Commissioner in February 2022 with a 50-46-1 vote and served through the end of President Biden’s term. The day of his confirmation, the Abbott infant formula recall began, sparking a nationwide infant formula shortage. It was also in the middle of the COVID-19 Omicron variant.

Through an Executive Order issued the day of his inauguration, President Biden required a bolstered ethics pledge for all his appointees, which included commitments not to accept gifts from lobbyists, favor former employers, or otherwise seek financial gain from government positions. For Robert, this pledge included committing to not seeking employment at any pharmaceutical company for two years after his term of service. Robert voluntarily extended it to four years. (As President Trump repealed this Executive Order the day of his inauguration, it is technically no longer binding.)

MAHA and an Alternative Route to Improved Health

In October 2024, now Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert Kennedy Jr. tweeted “FDA’s war on public health is about to end. If you work for the FDA and are part of this corrupt system, I have two messages for you: 1. Preserve your records, and 2. Pack your bags.”

In April 2025, the FDA laid off 3,500 employees. Current FDA Commissioner Marty Makary recently shared that additional layoffs may be coming.

Secretary Kennedy and his supporters have adopted the MAGA-adjacent slogan Make America Healthy Again (MAHA). In a May 2025 document titled The MAHA Report, Kennedy and Cabinet colleagues outline their agenda for HHS, committing that “After a century of costly and ineffective approaches, the federal government will lead a coordinated transformation of our food, health, and scientific systems.” The 73-page report made headlines for both its content and the subsequent realization that it cited false and nonexistent studies – it has since been reuploaded with corrections.

“MAHA was right to call attention to how America is on a highway not quite going in the right direction,” Robert shares. “Sometimes it is not as bad as they depict it though. American life expectancy was in the 60s in 1950 and now is 77. We had a gradual increase in life expectancy and quality of life, but we sort of stalled out, and I agree diet and exercise are critical. I feel vindicated here because I have been writing for 20 years about the tsunami of chronic disease. For whatever reason MAHA has people excited about it, so credit to them for that.”

Each year when Robert was Commissioner, his FDA team asked Congress for a larger budget for nutrition efforts, including to help improve food labeling and chemical assessment. Every year Congress denied this request. He is hopeful that nutrition efforts in public health might receive more support but is skeptical.

“The question is which fork in the road do you take? The one MAHA is advocating is full of nutraceuticals and miasma theory from the dark ages and all sorts of things like that. Even in the food arena, they are advocating for healthier food to some extent, but they are cutting the legs off Medicaid and SNAP, so that is only going to get worse for the most vulnerable people in our society who eat lousy food because that is what they can afford.”

Robert has a vision for an alternative route to a healthier America.

“I am in favor of doubling down on the things that we know work. Japan, Scandinavia, and Singapore have less chronic disease and higher life expectancy, so let’s do what they do: healthcare as a right with primary care as the base. We are the only high-income country where you have to earn healthcare as a right. We have a broken primary care system. Then we should go all in to support young families with strong parental leave, support children getting vaccinated, and help Americans control the simple risk factors like cholesterol, blood pressure, and not using combustible tobacco products. The MAHA Report also does not mention the leading cause of death for children, which is gun violence, or our major issue with drug overdoses. If you ignore the leading causes of death, then I’m not sure how you can find the right solution.”

Beyond the MAHA movement, Robert also notes other reasons why many Americans are skeptical of the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries, and by extension the FDA.

“I’m certainly not a proponent of the current status of drug pricing in the US, which is at the core of a lot of this distrust. If I were a king, we would not have pharma advertising on TV, but that has been through the courts, and the courts ruled that corporations have the same rights as individuals. I don’t think that is a reasonable judgment, but it is what happened,” Robert summarizes. “You have a situation with innovator drugs where they have much higher prices in the US and a lot of advertising, so marketing for these drugs is really profitable. There is an old saying that if you want to be trusted, you need to act trustworthy.”

Robert also identifies medical misinformation as a hindrance to American public health.

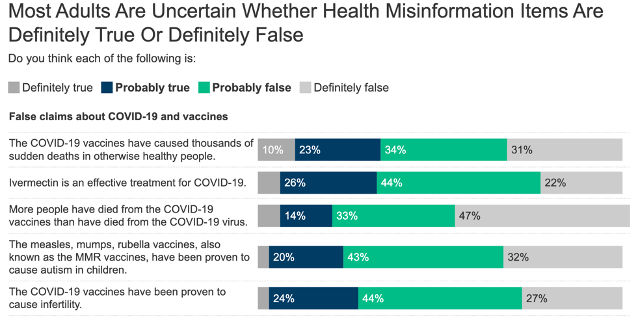

A 2023 KFF study found that 96% of surveyed Americans had heard at least one of ten specific statements of health or medical misinformation, including false statements about COVID-19. While a minority of participants identified as believing the misinformation, most were not confident whether presented statements were misinformed or not.

74% of participants identified the spread of false and inaccurate information about health issues as a major problem.

Most respondents flagged false statements about COVID-19 and vaccines as probably false.

Source: KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll, August 2023.

“We are losing the battle on misinformation right now in my view. One reason is that you can see a patient in the clinic for fifteen minutes and then they go home, and they get 24/7 misinformation from social media. It is hard to compete,” Robert emphasizes. “What people do have confidence in is the doctors, nurses, and pharmacists that they are actually seeing. It is the human contact that matters.”

Indeed, the same KFF study found that 93% of respondents noted that they trust their own doctor to provide proper health recommendations and to act as a source of truth. Respondents collectively ranked their own doctors as the most trusted source of medical information, above the CDC, FDA, state and local health officials, and both the Biden and Trump Administrations.

Chasing Gold: The Future of Biopharma Innovation in the United States

Since 2021, China has begun to exceed the United States in the number of clinical trials registered annually. In response an independent commission proposed policies to Congress to bolster the American biotech industry in April 2025.

“The future of innovation in the United States is not my biggest worry,” Robert shares. “We are congenital innovators; we are renegades – sometimes that comes out in bad ways. We grow up looking at problems and trying to get solutions, somewhat driven by the opportunity to make money, and that is a big part of our culture.”

Robert happened to have been one of the early faculty who helped establish Duke’s campus in China near Shanghai, which partially informs his view of the landscape.

“China has 1.5 billion people. We ought to work with them if we can versus just competing,” he assesses. “Still, it is a country run by a dominant, repressive central government which to some extent sees us as an enemy and has been stealing our trade secrets and fabricating data for a long time. China has a definite goal to be better than us in biomedical science because they see that as the future. That is one of the reasons that many of us are upset about the Trump Administration’s cuts to the National Institutes of Health and universities.”

These concerns were similarly voiced by Republican Congressman Philip Babin of Texas in a recent hearing about the American biotech industry. Congressman Babin is currently serving as Chairman of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. The hearing was titled “Pursuing the Golden Age of Innovation: Strategic Priorities in Biotechnology.”

Arguably, Robert witnessed the impacts of the existing Golden Age of American biopharma innovation more than almost anyone, including through his interactions with peer nations’ regulatory agencies.

“A great thing about being the FDA Commissioner was everywhere I went they said: the FDA is the gold standard, you guys in the US invent all the stuff, and we get to use it,” he recounts. “That is a good position for the United States to be. I think we will continue to innovate, but I don’t know whether we will remain the dominant innovators.”

Leave a comment