Interview with Dr. Dannell Boatman, Assistant Professor, Researcher

“Unless we understand what drives a person to make certain choices it is hard to meet them where they are and encourage positive behavioral change. I benefit by being from and within the Appalachian culture because I know that it is different than other places.”

– Dr. Dannell Boatman

TikTok: The Next Research Frontier

Like many, Dr. Dannell Boatman developed a pandemic project in 2020. Unlike most, hers stemmed from her lockdown TikTok consumption.

Amidst the stream of viral dance challenges and cat content, Dannell noticed another sub-genre of video: vaccine discourse.

According to the 2024 KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll, 20% of adults self-report that they use TikTok daily and 40% of TikTok users report trusting health information they see on the app. 15% of TikTok users identify that content viewed on TikTok has made them less confident in the safety and efficacy of vaccines.

As a health communication researcher, Dannell was alarmed by misinformation on HPV vaccines in her feed. This led her to launch a project with her team at West Virginia University (WVU) Cancer Institute’s Cancer Prevention and Control Program. Their research on HPV TikTok content has snowballed into several investigations of how health information is delivered online and how to combat health misinformation. Merck, which manufactures HPV vaccine Gardasil, even funded additional research from the lab.

While digital health misinformation affects a broad population, Dannell’s research primarily focuses on those living in the Appalachian region, as part of her role in leading the Communicating for Health in Appalachia by Translating Sciences (CHATS) Lab at WVU.

It may initially seem counterintuitive that a viral social media app predominantly used by Gen Z has a disproportionate effect on the mountainous interior East Coast, but when considering the rurality and healthcare access challenges in the region, it is understandable that Appalachians are at a greater risk for health misinformation on social media.

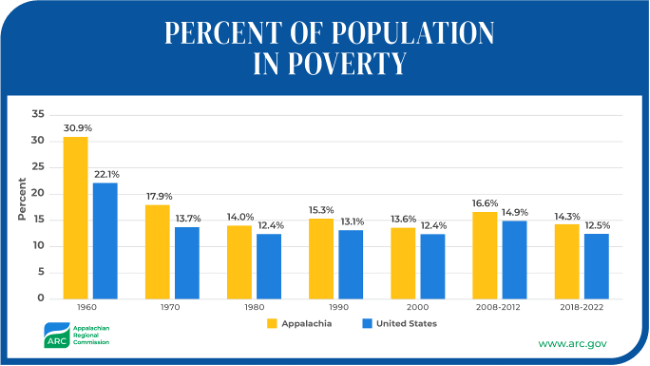

“It is important to know that there are certain populations that are more susceptible to misinformation, and those groups tend to have lower socioeconomic backgrounds. That is something that makes up the Appalachian region and West Virginia,” Dannell explains.

Dannell’s West Virginia

West Virginia (population: 1.77M) and Appalachia (population: 26.4M) are central to the origin stories of both the CHATS Lab and Dannell.

“I always knew I wanted to do something important to the region. I can’t really talk about my career unless I talk about where I’m from,” Dannell prefaces. “Living in West Virginia is one of the most defining characteristics of my life.”

Dannell grew up in Monongalia County (population: 108,000) just south of the Pennsylvania border in a “rural but busy” part of the state.

Mon County, as it is known, encompasses Morgantown (population: 30,000), where WVU is located. As a first-generation college student, Dannell felt a bit directionless initially when she attended WVU as an undergrad. She found inspiration within the Communication Studies Department that led her to a post-grad communication role at the WVU Cancer Institute.

While working at the Institute, Dannell earned two master’s degrees in adult education and health communication as well as a doctorate in education. After completing a post-doc, she established the CHATS Lab in 2022 and received her academic appointment with the School of Medicine in 2023.

“I feel that it is important to be targeted with how we reach people. So much of what drives my work is health behavior change frameworks and models. Unless we understand what drives a person to make certain choices it is hard to meet them where they are and encourage positive behavioral change,” Dannell explains.

“Understanding the perspectives and culture surrounding an individual and how they make their health and life choices is critical for anyone interested in health change,” she elaborates. “If you went to another state and tried to do an intervention focused just on the individual that might be effective in that culture, but in Appalachia it is not as effective as we need to bring friends and family into that decision.”

Almost Heaven: West Virginia

There is a lot to love about West Virginia.

It has the uniqueness of being the only “West” state in the nation following its Civil War breakaway from Virginia.

The landscape is beautiful, attracting tourists to its winding highways with panoramic views of mountain foliage.

John Denver’s Take Me Home Country Roads is an official state song. And for anyone doing a close listen, the lyric about life being older than the trees is literal – the Appalachian Mountains covering the state are millions of years older than the first trees.

Famous West Virginians include comedian Don Knotts who played Barney Fife on The Andy Griffith Show, television all-rounder Steve Harvey, and elusive folklore sensation Mothman.

Dannell also vouches that the community is unparalleled.

“I promise you West Virginia is not just negative statistics. It is a warm place with a strong sense of community,” Dannell describes. “There is this connection to place and community that you cannot get elsewhere.”

Despite this, adversity seems to be the facet that lingers most in the mind of the rest of the country. The state struggles with poverty, but media representations often distort this into an exaggerated caricature.

“There are many stereotypes about West Virginia that are hurtful and embarrassing to people who live in the state. We are frequently characterized as hillbillies that are uneducated and live in extreme poverty,” Dannell reflects.

According to the 2023 census, 16.7% of West Virginians live in poverty compared to the national average of 11.1%. At ~$54,000, the state’s median household income trails the national equivalent of $80,610.

WVU’s 2022 West Virginia Economic Outlook Report noted that only ~55% of West Virginian adults are currently in the workforce, making it the state with the lowest labor force participation. West Virginia’s population is also in decline, with a population loss of ~73,000 residents from 2012 to 2021. The report’s authors cite the opioid epidemic as one contributor for both outcomes. In 2022 the state had the highest drug overdose death rate with 80.9 drug overdose deaths in West Virginia for every 100K people compared to the national average of 32.6 per 100K.

Simultaneously, there is an abundance of natural resources in the state. West Virginia’s economy has long been intwined with energy production. According to the US Energy Information Administration, West Virginia accounted for 6% of the nation’s energy production in 2021. In 2022, West Virginia was the second greatest coal-producing and fourth greatest natural gas-producing state. West Virginia was one of only five states that exported generated electricity to other states. The state also exports coal internationally; Ukraine and China are major customers.

Despite the outsized impact that energy resource production has on the economy, only 3% of West Virginia’s workforce was employed by the sector in 2021. In comparison, 10% of West Virginia’s workforce mined in 1979. Currently the local economy is adapting to the decline in domestic coal demand, which is largely driven by its environmental costs, with the state making efforts to expand renewable energy capabilities, including electric battery production.

Source: West Virginia University, West Virginia Economic Outlook 2023-2027, Bureau of Business and Economic Research, utilizing US Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

So if West Virginia is so well-resourced, why does the state experience such high rates of poverty?

Poverty is rarely single-sourced. However, it is certainly relevant that much of the resources within the state are owned externally.

In 1974, investigative journalist Tom Miller with the Huntington Herald-Dispatch conducted a systematic review of land deeds in the state. His study found that approximately two dozen out-of-state corporations and mineral production organizations owned ~33% of the state’s private land. He also found that out-of-state companies owned over half of the land in about half of West Virginian counties and that none of the ten largest landholders were headquartered in the state. In 2012, researchers conducting an updated review found that 25 entities owned ~18% of the state’s private land. These studies and others are summarized in the 2013 report “Who Owns West Virginia?” from the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy.

Appalachia: A State and A Region

West Virginia’s Appalachian identity is core to its culture, but what does that mean?

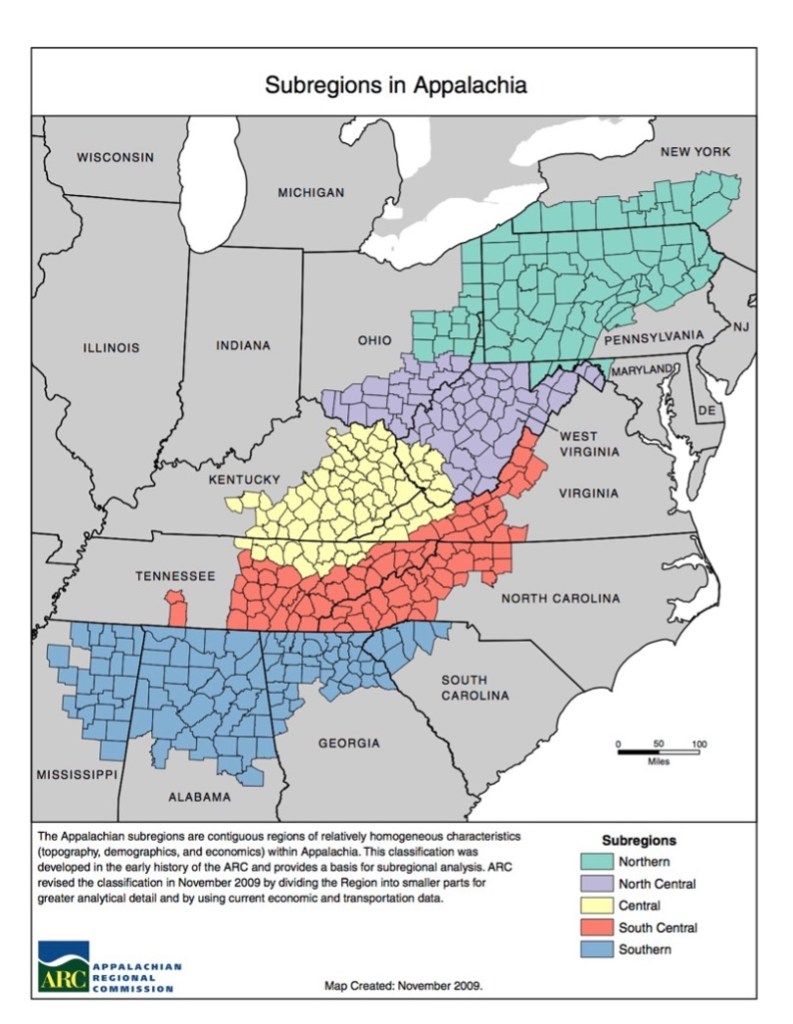

The Appalachian Mountains extend from Alabama to Canada, but the Appalachian region cuts off in New York. The Appalachian Regional Commission makes this distinction based on both geographic features and the socioeconomic climate. Appalachia encompasses 13 states, but West Virginia is the only state entirely within Appalachia.

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, “Subregions in Appalachia.”

The mountains create a natural obstacle, making access and transportation to key services burdensome. The landscape tangibly impacts economic opportunities in the region. Many workers flocked to the region following the Civil War as industrialization efforts led to a boom in the demand for timber and coal, but as this has reversed over time, access to strong jobs remains a regional challenge.

“Many rural areas have access issues, but access is even harder in Appalachian counties. This is a really disadvantaged population that needs special attention,” Dannell summarizes.

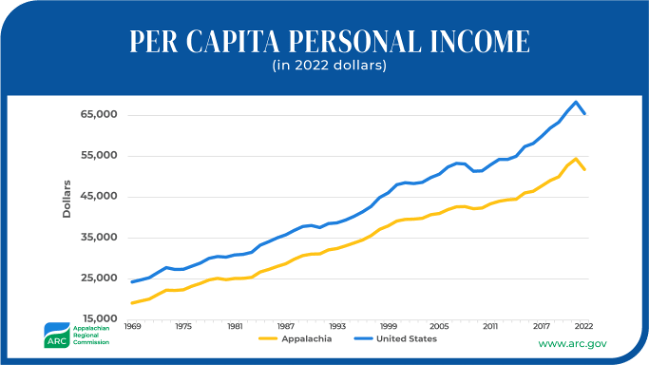

As a result, the Appalachian economy has historically trailed the rest of the country.

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, “About the Appalachian Region”

Communicating Science, Building Accessible Healthcare

In West Virginia obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are prevalent and persistent. In 2022 West Virginia had the third highest rate of deaths from cancer in the country with 176.3 deaths per 100K per the CDC.

The CHATS Lab studies and creates health communication initiatives, particularly focusing on health behaviors tied to cancer incidence and mortality.

“A lot of our work is developing more effective strategies to reach populations that we are trying to get to do a behavior, like lung cancer or colon cancer screenings. Each step of the way, we have people from the population engaged in the process – whether through surveys, focus groups, or interviews. You don’t get people to change behavior or improve health if you just talk at them. You want to bring them into the conversation, into the research and work together to develop interventions that are tailored and targeted,” Dannell notes.

A big part of the CHATS Lab ethos is its emphasis on culture.

“Effective public health practice in West Virginia harnesses our strength of community and connectedness. There is a strong sense of pride and self-reliance that underscores so much of what we are in West Virginia, and I don’t think you can be effective in health research in a state without understanding the cultural characteristics that make it up,” Dannell reflects.

The CHATS Lab team works with the Mountains of Hope (MOH) statewide cancer coalition. MOH brings local organizations together to facilitate cancer prevention, early cancer detection, and quality of life improvement for those with cancer. The organization also writes the state’s strategic five-year Cancer Plan in collaboration with patients, caregivers, and local government.

“Broadly to address our health challenges we need a comprehensive approach that addresses both the structural and psychosocial barriers through policy and programs that are targeted to the unique characteristics and needs of the state,” Dannell emphasizes. “It is a significant undertaking to do this. It is moving mountains.”

It is also what Dannell, CHATS Lab, WVU Cancer Institute, and MOH are trying to do.

In recent years, MOH grants have helped fund an online smoking cessation tool, a program providing cancer patients with fresh meal kits with local produce, and an at-home exercise guidance program for cancer patients.

WVU Cancer Institute’s mobile cancer screening program bridges access gaps in cancer prevention. Bonnie’s Bus Mammography Unit and the Lung Cancer Screening Unit (LUCAS) leverage a refitted bus and semi-truck to help remote patients screen for high prevalence cancers.

“We know that we have issues with cancer screening and transportation access to services, so these big mobile units travel across rural roads to meet people where they are in their community and screen them,” Dannell explains.

WVU also participates in Project Extensions for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), a model developed at the University of New Mexico that facilitates specialized medical knowledge sharing in rural healthcare systems via videoconferencing across a hub-and-spoke network. WVU’s Project ECHO utilizes the model to bolster local primary care efforts in epidemiology (i.e., Hep C, HIV), chronic pain management, psychiatry, endocrinology, and more, where dedicated providers may be few and far between.

Home from the Outside

In academic settings, Dannell frequently hears that she is the only person from West Virginia that her peers have met. Dannell takes that seriously.

She remembers a vivid moment in high school when a fellow student at a national conference learned she was from West Virginia and feigned surprise that she wore shoes, leaving a lingering hurt.

“Today when I go to national conferences, I am not just representing my work. For what it’s worth, I always try to represent West Virginia well,” she commits.

Recently Dannell moved to Ohio for her husband’s work, placing her right outside of Appalachia. She now works remote and travels to WVU often.

“Moving outside of Appalachia made me appreciate and love the state and people, the pace of life, and the tightknit community even more. You just cannot find that anywhere,” she emphasizes. “My work is still focused on West Virginia and Appalachia, so I am glad that I have that connection but being outside gives me a whole new appreciation for what I have.”

Leave a comment